Before I begin, a quick note on capitalization: I remain conflicted about the best management of the letter ‘B” in black. I initially decided to capitalize it based on this, but then decided a lower case “b” was best after reading this July 4th letter. In either case, what follows is offered with a spirit of respect.

Dear white people,

Yet another series of tragedies in the relentless torrent of violent actions directed against black and brown people shines a light on racism in our country. Once again we’re looking into eyes of hatred, unable to understand. Once again, we grieve as we hold tightly to the belief that love will win over hate eventually, but we don’t know how to make the journey. How can we fix what is so terribly broken in our country? I don’t have the answer, but I have some thoughts that I believe could help guide us toward it. First, though, here’s some context for my perspective.

My friendship with Dorothy Pitman Hughes helps me see things I’d be blind to otherwise. Dorothy’s a veteran civil rights and feminist activist who has worked tirelessly for social justice since her early days growing up with Jim Crow laws in Stewart County, Georgia. In the late 1950s, Dorothy relocated to New York City and organized community resources to provide affordable childcare, job training, education, housing and food for struggling families. Her work captured the attention of Gloria Steinem who interviewed Dorothy and then wrote about the needs of black families in an article in New York Magazine. The two worked together speaking and organizing for a decade and have remained dear friends and collaborators ever since.

I met Dorothy in 2008. Since then we’ve shared hundreds of hours of conversation. Early on, when Dorothy would share her perspective and invite me to understand things in the context of her experiences, she’d reveal how racism influences outcomes in subtle and not so subtle ways. Most often I couldn’t see the subtleties. I didn’t actively resist seeing them, but they just weren’t visible to me. So I listened. I trusted the validity of her observations. I asked questions and worked to connect with her ideas. Over time, I began to see some things I’d been blind to previously. Listening to Dorothy opened the way for me to begin seeing a reality that was too nuanced to intuitively stand out against the backdrop of my personal experience. I had to invest time, contemplative energy and trust to bring the picture into view. The journey for me continues.

At this point in writing, I find myself imagining the variety of responses that might follow. My thoughts travel to a scene in the book, Space Race I: Solar Flare. Two characters engage in conversation, Raglin, an Earth-born human who hates the space-born labor-class humans called the loxies, and Nanley, an Earth-born human who regards loxies to be just differently experienced people in a vast humanity. Here they discuss one loxie’s keen ability to maneuver objects in deep space, instinctively seeing paths that Raglin and Nanley are unable to see:

“When I was a kid,” said Nanley, “My uncle—a real waterman, he fished for a living—he’d take me fishing. He spent his whole life on the water. He’d see fish under the surface twenty, thirty meters away and tell you what kind. I’d be looking at the very same place and not see a thing.”

“Yeah, probably full of shit,” countered Raglin, gesturing. “There’s some cod, there’s some pike, oh, and there’s the Loch Ness monster!”

“I called it bull at first, too—cow-tipping, snipe hunting, that sort of thing ‘til I spent a summer on the bay fishing. By August, I could see maybe a hundredth of what he could, but I could see it…the loxies…they see things in ways we don’t—watermen in their own right. Watermen of the infinite sea.”

I’m reminded of the scene because today, in 2015, when a black person sees racism that a white person cannot see, it’s far too common for the white person to label the black person as hypersensitive. And it’s far too rare for the white person to recognize the action of labeling for what it is: indifference to systemic racism and defense of white people’s blindness to realities that fall outside of their detectable range.

I’m overwhelmed by the legacy of violence and discrimination in our country and often feel powerless to help move humanity toward a socially just world, but an email conversation last summer opened my eyes to the enormous power of listening. It gave me reason to believe we can get there, if we have the will.

A member of a minority community, for which most community members have endured human rights violations since the day of birth, generously provided firsthand insight relevant to a TEDxJacksonville talk I was developing. After I delivered the talk, I sent the transcript and received this reply:

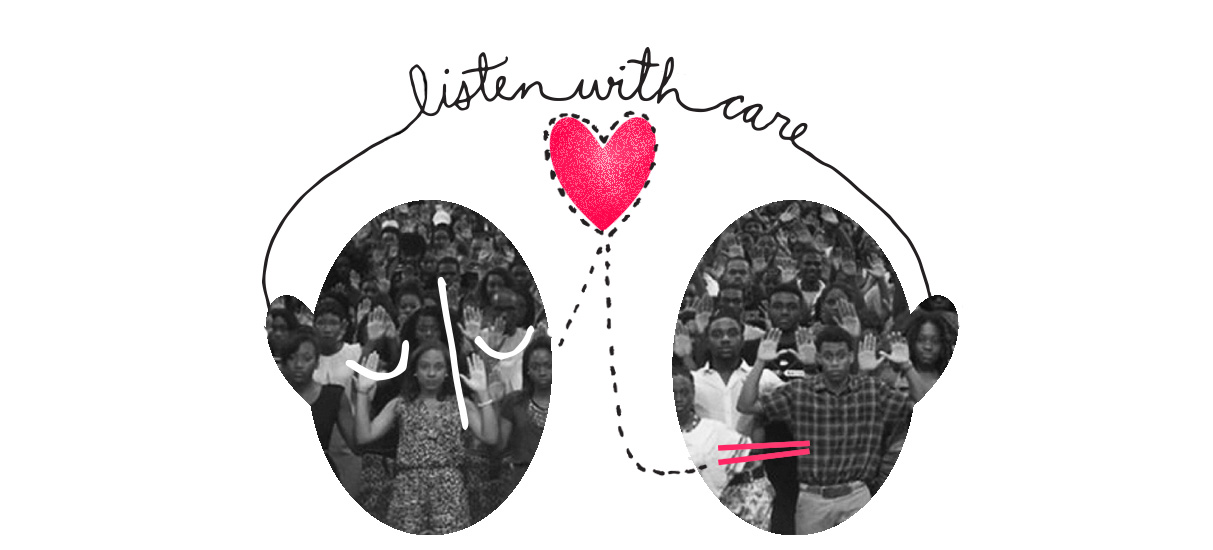

“I did not expect you to listen with care, but you did, and it was a relief. Thank you.”

I lingered on the words. Listen with care. Wow. It was a relief. The simple, powerful act of listening gave relief and rewarded me with hope.

The words reminded me of the norm: members of underpowered (minority) community groups have grown so accustomed to people not listening, that the rare experience of being heard sometimes evokes relief and gratitude. The words also reminded me that the first step in solving a problem is to understand the problem. An obscured or distorted view of a problem makes it nearly impossible to understand it. Listening with care offers a way forward.

We have real, tough problems with root causes that are complicated, emotionally charged and deeply embedded within cultural narratives. Our only hope for uncovering durable, sustainable solutions is to do whatever it takes to build bridges of trust and the job of bridge-building begins with us: white people.

Listen with care is a call to action made urgent in the endless wake of the latest episodes of violence, reminders that our country’s racist past remains present today. Over and over a pattern plays out. Tragedy inflicted upon black bodies reignites the fire of raucous debate, not directed at finding real solutions, but, instead, fueled by our cultural appetite for drama as entertainment; in other words, sport. We bear witness from safe distances, entranced by dramatic footage playing on a screen or served up as the backdrop for political and social commentary. Images cast a light on the plight of underpowered citizens and we respond. But not by listening. Instead, we broadcast.

Like a primitive reflex, we start talking. We mix scolding messages about responsibility with worn-out, authoritative rhetoric that presumes to set the record straight about how things are, why they happen and what matters. We jockey for the biggest bullhorn and try to out-shout anyone whose words and actions refuse to validate our ideas. Trending topics flood social channels where the crowd behavior looks more like screaming fans at a sports event than a conversation between citizens trying to solve serious social problems. Any hope for civil discourse drowns in the flood.

We’re masters at talking and we’ve built an incredible infrastructure to make sure our talk is heard across our nation and around the world, but what we need now more than ever is even more powerful listening.

Most of us desire to live in a society where social justice is afforded to all citizens. While trying to move toward that, we think we’re listening and we think we’re engaging constructively in public discourse, but a long list of outcomes suggests we’re falling short of our intention. What does that look like?

Not listening with care sometimes looks like…

…waiting to talk, politely staying quiet until the speaker pauses, focusing on constructing our response or loosely filtering the speaker’s words to uncover something that might reinforce our counterargument. Waiting to talk keeps us from hearing the speaker and blocks any potential for empathy or authentic connection. The chance to understand is lost, shoved aside by the pursuit of a fleeting debate victory.

…changing the subject. Contentious subjects, like race and class divides, evoke strong emotions and make many of us uncomfortable. Changing the subject is a pretty common “autopilot” response. When we change the subject and leave contentious subjects behind, we may feel more settled, but the price for our short term comfort is the silencing of the voices of those for whom leaving behind the issues of race and class is not an option.

… spotlighting fragments of a story or cherry picking information that perpetuates stereotypes. We can’t include every detail when we share a story, so we’re forced to make choices. Even when we’re motivated to give a complete and unbiased perspective, it’s extremely difficult to avoid introducing bias as our mental filters make unconscious choices. When we recount someone else’s story, share a sound bite from their full account of events or select and post a story on a social media channel, we’re functioning as stewards of a person’s, or in some cases, a nation’s story. Awareness of our stereotypes and how they influence what we see and hear and how we assign meaning is a big step toward being able to listen with care.

… discrediting the speaker. This is a particularly troublesome version of changing the subject. Imagine meeting with your boss to resolve a conflict you have with a particularly charismatic coworker. You attempt to offer your perspective, but your coworker engages your boss in a lively conversation about a professional misstep that had been addressed during your last performance review and is unrelated to your current grievance. You take your grievance to human resources and encounter an identical scenario. Eventually you realize everyone who might help you resolve your grievance is distracted by your coworker who is creating a spectacle of your past, unrelated infraction. Discrediting the speaker neutralizes the impact of a speaker’s message so effectively that civil rights leaders in 1955 held out for “the perfect victim” before mobilizing around Rosa Parks as a strategy for ending bus segregation.

…demanding politeness. Comfort. That’s what drives the demand for most of us, although for some, demanding politeness is a calculated ploy to discredit the speaker. In either case, demanding politeness is a refusal to listen to the message if the messenger’s tone doesn’t fulfill our needs. Demanding politeness misses the opportunity to listen and begin bridge building. It’s about us. Again.

…ignoring the speaker. This plays out in face-to-face and online conversations. When we choose to read and listen to perspectives that only serve to reinforce what we think we know, we miss the opportunity to learn from points of view that can give us access to a more complete understanding of how things are.

…buying silence. Paying over a hundred people who were adjudged to have been victims of police brutality almost six million dollars over a four-year span and prohibiting them from making public statements or talking to the media ensures that those collective voices will not be heard. When one is struggling financially, choosing to accept a financial settlement in exchange for silence is a predictable outcome.

…emotional reflex. We’re humans. We experience our world emotionally. When we allow our emotions to drive our engagement with marginalized groups, then it’s about us. It’s about reinforcing our core beliefs and staying comfortable, not about listening with care and discovering alternative perspectives. During the events that surrounded Freddie Gray’s death in Baltimore, Maryland, a poignant example of emotional reflex emerged as a mother was labeled “Mother of the Year” and the “hero of the Baltimore riots.”

…felonization. Our vote is our direct political voice. Tough-on-crime laws and the school-to-prison pipeline that feeds into our growing for-profit prison industry, disproportionately enters minority populations into our criminal justice system and convicts them of felony-level crimes. Loss of their right to vote due to felony convictions weakens the collective voice of minority communities.

…outsourcing discovery. Misguided efforts to teach children color-blindness, school curricula that reinforces destructive racial stereotypes and social behavior that is largely segregated by race have created the perfect storm for generations of culturally incompetent white people. But here’s the rub: we can’t outsource the responsibility to become culturally competent. Racially socializing us is not the job of minority community members who endure the negative outcomes of our incompetence. Learning is our job. Luckily, there are some guides who have stepped up to point us in the right direction.

…ignorance of the price paid for our comfort. Still today, as we did in the past, we send clear messages that we don’t tolerate black people’s anger or rage. And because the power cards are in our hands, we set the price that black people pay to stay safe or get ahead: forgive and move on. Keep us comfortable. The pattern continues. It’s about us again.

…appropriation. Understanding this variety of not listening has been a gradual, multi-step process for me. First I made the choice to believe. I trusted that the perspectives Dorothy and other black friends brought forward were credible, valid and insightful. I listened and read to expand my context for pondering the ideas I was hearing. Gradually patterns and details came into view that allowed me to begin parsing subtleties and to begin seeing the impact and significance of the power dynamics. As I listened to conversations in reference to Rachel Donezal’s actions, a clear, obvious and coherent picture finally emerged.

Two outcomes—grabbing potential benefits and hijacking the narrative—reveal how appropriation is the antithesis of listening with care. Both exact a heavy toll on marginalized groups.

- Grabbing potential benefits plays out in predictable ways. Competition for a scarce supply of opportunities and resources is fierce. Even tiny differences in power can be leveraged to create significant advantage. Like an elaborate Rube Goldberg machine, the consequences reach far beyond the initial impact, especially for intangible resources, such as:

- Share of attention: In our noisy world, competing for public attention is daunting.

- Share of market: With countless numbers of choices, turning listeners into buyers requires way more than just delivering quality services or products.

- Influence: Our capacity to effect outcomes often depends on access to decision makers, trusted credentials, positional respect and other factors. Influence wields power in epic proportions.

- Strength of affinity: The degree to which people spontaneously and naturally like or connect with us increases with familiarity, so visibility in association with respected organization confers advantage.

- Hijacking the narrative: Whoever controls the narrative controls public opinion, and public opinion strongly influences policy; the stakes are big when it comes to narrative.

There are no sidelines: Inaction, silence and not listening with care all tacitly advance racism. Ideally, our motivation to contribute to the solution alone would move us to instantly achieve cultural competence and compel us to become engaged activists. But that’s not reality. It’s unconscionable to advance racism, but at the same time, it’s genuinely hard to fight what we can’t see. It looks like we’re faced with a double bind, but we’re not.

Step briskly forward with purpose and a plan

We can listen with care, take action and use our public voice strategically by taking the following steps:

- Make a commitment to work toward building bridges of understanding and connection to help fix our fractured culture.

- Reach beyond our front porch view and shake free of the notion that our personal majority experiences provide a reliable benchmark for understanding or judging the actions and behaviors of marginalized others.

- Notice our responses to what we hear and see and practice recognizing when we’re not listening with care.

- When the actions, words or perspectives of marginalized community members conflict with our point of view, suspend our disbelief and actively listen with care. Stay patient. Trust the validity of the perspectives. Search the internet for thoughtful commentary, written or recorded by minority community members, to guide our exploration of the conflicting ideas.

- Dare to accept personal vulnerability. Drop our defenses, open our minds and direct our bravery toward developing the skill and confidence to defend marginalized others.

- When we discover resources that enhance our understanding, share them. If we feel compelled to analyze or interpret the words of the person who created the resource, hold back. Type #ListenWithCare, instead.

- Allow new insights to help us navigate our way forward.

Peace —

Judi